Human civilization requires web mapping services in order to function smoothly. More than one billion people per month use Google Maps, and that’s just one web mapping service. Web mapping services aren’t only for directions to your friend’s new place, but for package tracking and large-scale logistics.

All these map apps rely on geographical information systems (GIS) that provide the data these apps use to orient people. But this technology is only helpful as long as the data are faithful to the environment. Geographic information science researchers warn this technology could become the target of deepfake geography.

Chengbin Deng—Associate Professor of Geography at Binghamton University—and his colleagues at University of Washington and Oregon State University have sounded the alarm on this possible manipulation of geospatial data.

“Honestly, we probably are the first to recognize this potential issue,” Deng told BingUNews.

Deepfakes, an AI technology

Deepfakes are most popularly known for their role in creating modified video content. The proper name for deepfakes—from “deep learning” and “fake”—is synthetic media. Such synthesized content is produced by artificial intelligence, and has seen a major upsurge in recent years due to an advance in machine learning known as a generative adversarial network (GAN).

GANs work so well in part because their outcome is based on a competition. The machine learning framework pits two neural networks against each other. First is the generator. Second is the discriminator. Together they perform the duties of a creator and a grader. A GAN is given a training set—for example, photos or videos—and the creator’s role is to fool the grader.

To illustrate, take a look at the above image. The man on the right does not exist. It is an example of synthetic media. To create the image, I selected and uploaded a photo from Pexels (left) to a GAN service called Artbreeder. Using some control manipulations, Artbreeder changed the eye color, the age, emotions, and reduced facial hair. And this is a very subtle use of the tools available.

Deepfake Maps

To the casual observer, Artbreeder or similar GAN images might not ring any alarm bells. These are certainly fun tools for the artistically-inclined, but such images are no longer uncanny. In fact, a team headed by Max Planck Institute researcher Nils Kobis showed people cannot reliably differentiate real videos from deepfakes.

Deng et al. believe the same could hold true for GIS data, if the industry does not prepare.

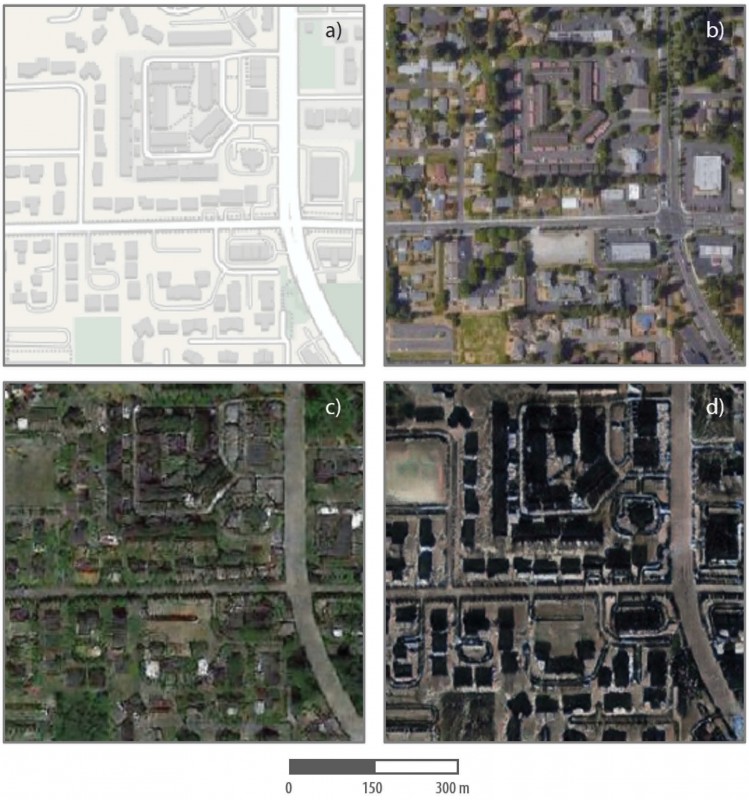

In their article, the researchers set out ways to detect fake images by creating some of their own. A smarter, outside grader to detect deepfake creators. In their synthetic map, they tested 26 metrics for statistical differences, and were able to mark 20 as anomalous.

To start, 80% sounds pretty good, but the team warns their detected differences—roof colors and image sharpness—depend on the inputs. Similar to Artbreeder, controlling these inputs could produce more realistic fake images.

The researchers conclude that they have only opened the door on this problem. This is the beginning of a serious fight against misinformation. A systematic approach will be necessary to unveil fraudulent data before geographers can validate and release information to the public.

As Deng told BingUNews, “We all want the truth.” And we’ll have to fight to preserve it.